Unsafe Foods: Web Scraping and Key Matching

The Unsafe Foods project is going to be very exciting and challenging this summer. We get to experiment with advanced text mining practices and attempt to make a predictive model for product recalls from Amazon reviews. As intriguing as this topic is, our goals will not be achieved without a lot of sifting through some muddy data sets and determining what we can accomplish given our time frame and resources.

For the first week of the Unsafe Foods project, our team had to figure out how to grapple with two separate data sets with very different formats. For the Amazon review data, we are using a structured data set curated and published by Julian McAuley from UCSD. The challenge arose in capturing a workable data set for food recalls from the FDA. Kara Woo managed to find an XML version of a history of food recalls with a link to each recall's press release containing each product's unique identifier(s).

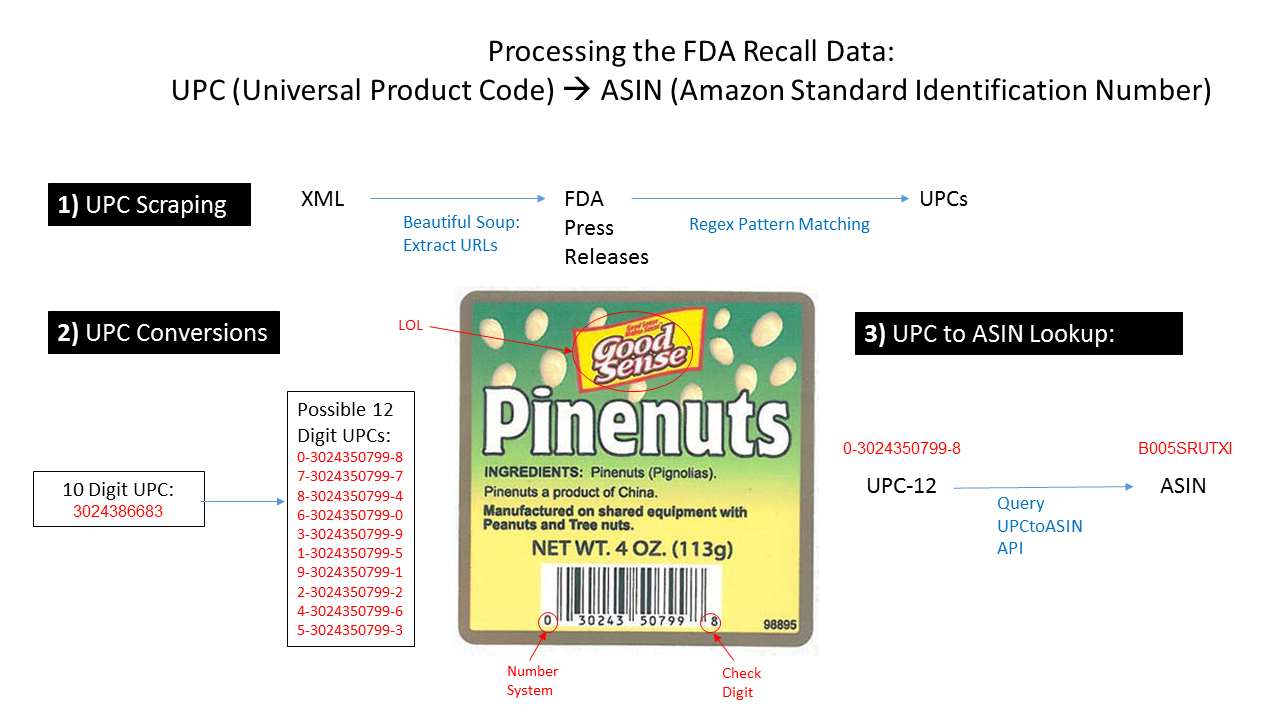

These data sets required some creativity in order to bring them together. Each Amazon review was assigned an ASIN, or Amazon Standard Identification Number. Each ASIN corresponds to 1 UPC, or Universal Product Code. Unfortunately, while the Recall XML data contains unique names, the UPCs are listed only when available, and in no particular format within the press releases. We needed to figure out a way to capture those UPCs to match them against the reviews' ASINs.

After looking at several press releases (more or less) at random, we developed some regular expressions to capture the UPCs as best as we could. We performed web scraping on each press release page using Python's BeautifulSoup module and developed a corresponding list of UPC lists (since many products had multiple UPCs for different flavors, sizes, etc.), captured by the regex patterns.

Once we had a collection of UPCs, we then needed to find their corresponding ASINs. Fortunately, there is a 1:1 relationship between UPCs and ASINs. We just needed the ability to convert them. We found a REST API that would allow us to automate the process of passing in UPCs and collecting their corresponding ASINs. However, this was probably the most challenging leg of the task. There were two major issues:

The first issue was overcome just by splitting up the UPCs so that we each performed a quarter of the conversions on our separate IP addresses. However, this issue could have been avoided if we had already migrated our project to AWS so that we could let longer jobs run overnight or create multiple instances quickly and easily.

The second issue was trickier. We had to research the nature of the UPC, and figure out if there was any way to determine the corresponding 12-digit UPC from the provided 10-digit format. Miki Verma saved the day, though, and she figured out an algorithm to determine the 10 possible 12-digit UPCs from the 10-digit UPC. From there, we can infer that there is only one possible 12-digit UPC among the 10 possibilities. This is because the first digit is based on the type of food, the next 5 digits correspond to the company ID, the next 5 digits are reserved for the company-wide product ID, and the last digit is a check digit to confirm the validity of the UPC. With the 10-digit UPC, the company ID is known, and the product ID is known. Each product has only one possible first digit. Once the correct UPC is passed into the REST API and a corresponding ASIN is returned, the function can discard the rest.

Now that we have found corresponding unique identifiers, we are able to tag our documents in order to develop a classification model. We hope that we can use this to make reliable predictions about the safety of food products, but we still have a long way to go!