Analyses & Conclusions

Topic Models

One significant contribution from this work is providing a categorization of content on these platforms. We used an unsupervised learning method called Latent Dirichlet allocation. This technique assumes that each post or comment is comprised of a mixture of topics and that each topic is a mixture of words. By looking at the co-occurence of words, we then hand-labeled these topics.

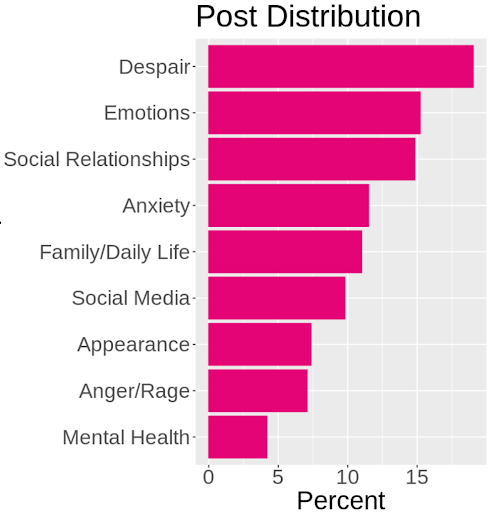

Based on fit statistics, we found that there were nine distinct types of posts that users made, the most common of which was an expression of despair. A synthetic example of despair may look like “Sometimes I get so lonely…then I get angry for feeling this way.” Other themes we detected corresponded to strong emotions, concerns about relationships, and generalized anxiety.

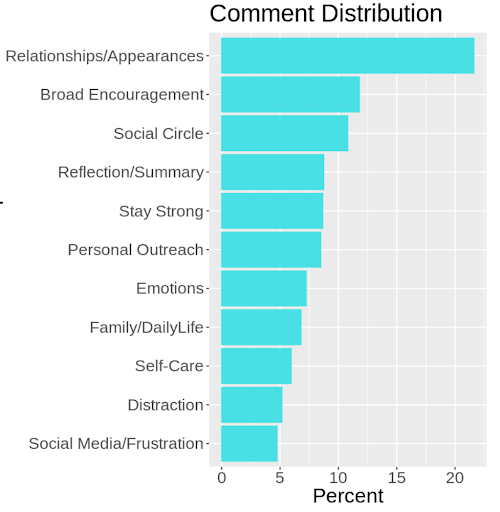

We also performed the same topic model analysis on comments and identified 11 distinct strategies that commenters used in responding to the above nine topics. The most common strategy was to relate their own personal challenges regarding relationships and their own self-image. The next most common category was a strategy we describe as “broad support.” This entailed offering supportive but general statements along the lines of “You can do this!” or “I know things are hard right now but you are strong and I believe in you.” Other strategies users engaged in include other forms of encouragement and personal outreach. Notably these topics do not map to typical counseling.

We also performed the same topic model analysis on comments and identified 11 distinct strategies that commenters used in responding to the above nine topics. The most common strategy was to relate their own personal challenges regarding relationships and their own self-image. The next most common category was a strategy we describe as “broad support.” This entailed offering supportive but general statements along the lines of “You can do this!” or “I know things are hard right now but you are strong and I believe in you.” Other strategies users engaged in include other forms of encouragement and personal outreach. Notably these topics do not map to typical counseling.

Motivational Interviewing

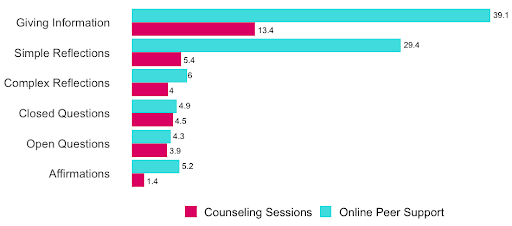

One of things we explored was the extent that commenters’ behavioral strategies mirrored those of clinicians or extensively-trained volunteers. Using a pre-trained machine learning algorithm, we labeled the data for the presence of motivational interviewing techniques, such as open-ended questions, offering affirmations, demonstrating reflective listening, and/or summarizing a session’s themes. A simple comparison between the peer support platform’s data and an analysis of clinical data indicated that these data exhibit different distributions. Namely, we found that counseling sessions are much less likely to include offering information than a peer support platform. We also found that reflection and affirmations tend to be more common on the peer support platform [1].

User Characteristics

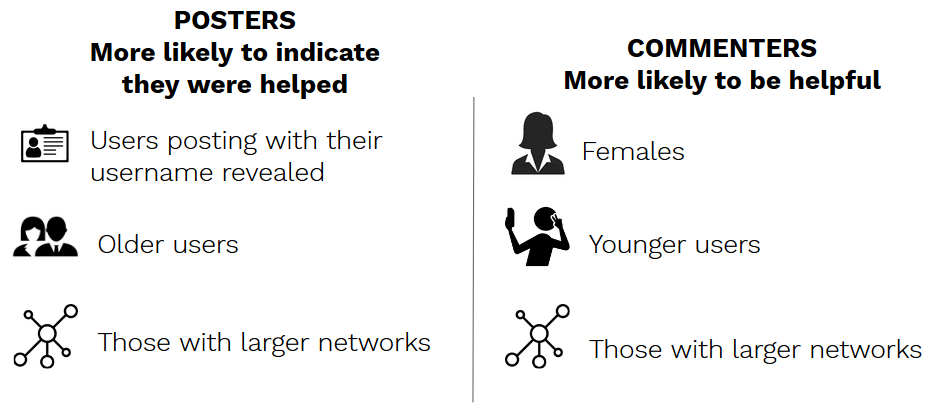

We found that users that did not go anonymous, older users, and those with larger networks on the platform were more likely to use any of our helpfulness proxy measures. On the other hand, female users, younger users, and again those with larger networks were more likely to receive any of our measures of helpfulness.

Thus user level characteristics did have some effect on our helpfulness indicators and needed to be controlled for.

Counseling Behaviors

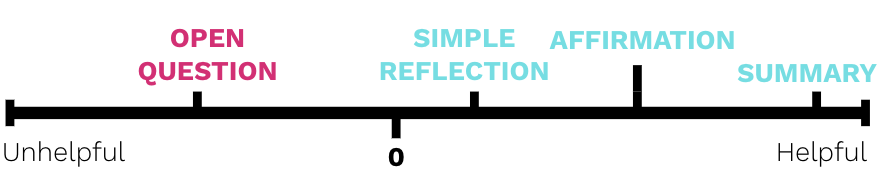

We then looked at how the counseling behaviors that we identified within our dataset mapped to our helpfulness proxies. In particular, we wanted to look at whether the use of motivational interviewing techniques by peers on the platform resulted in a greater likelihood of a helpfulness outcome. While we found that affirmations, reflections, and summaries do correlate positively with our helpfulness proxies, the technique of using open questions was not perceived as helpful on the platform (aka less likely to be liked/thanked/etc.).

We then looked at how the counseling behaviors that we identified within our dataset mapped to our helpfulness proxies. In particular, we wanted to look at whether the use of motivational interviewing techniques by peers on the platform resulted in a greater likelihood of a helpfulness outcome. While we found that affirmations, reflections, and summaries do correlate positively with our helpfulness proxies, the technique of using open questions was not perceived as helpful on the platform (aka less likely to be liked/thanked/etc.).

We do have a few theories for why this may be the case. Traditional counseling is, of course, a longer back and forth conversation between two individuals and thus utilizes open questions as a useful technique to bring out more information about the client’s circumstances. In contrast, our peer support platform only involved short interactions, so it’s possible that open questions are less useful in this context.

Furthermore, the one outcome that did correlate positively with open questions was “follows”. A potential explanation for this may be that open questions lead to further discussion in private chats, and private chats are more likely to result in follows. However, this is purely conjecture as we did not have access to data about the private chats on the platform.

Original Posts

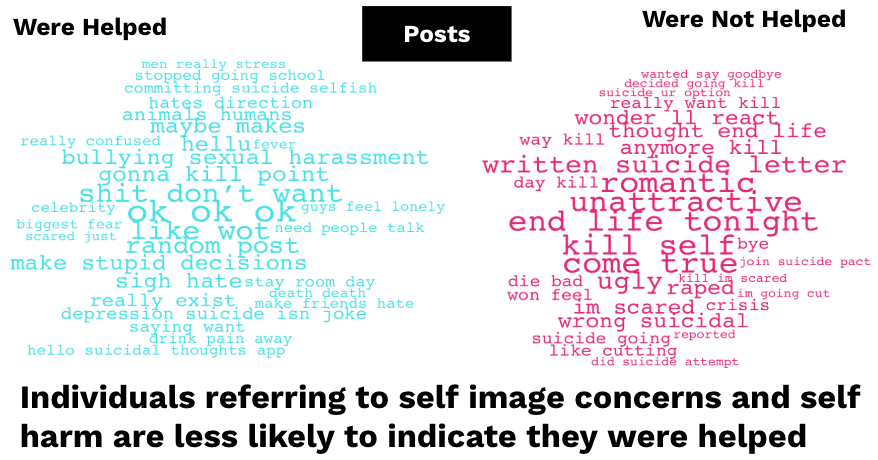

We also looked at the content of the posts in our mental health dataset in order to better understand what kinds of posts would elicit helpful comments. We found that while negative emotional content and despair is widespread, when individuals talk about self-image in particular (that they find themselves unattractive or ugly) or refer to suicide or self-harm, they are less likely to later indicate that they were helped.

We also looked at the content of the posts in our mental health dataset in order to better understand what kinds of posts would elicit helpful comments. We found that while negative emotional content and despair is widespread, when individuals talk about self-image in particular (that they find themselves unattractive or ugly) or refer to suicide or self-harm, they are less likely to later indicate that they were helped.

This brought up a potential issue of bias within our helpfulness proxy measures: are users who are discussing darker/more challenging circumstances less likely in general to use things like likes, follows, gratitude, etc.?

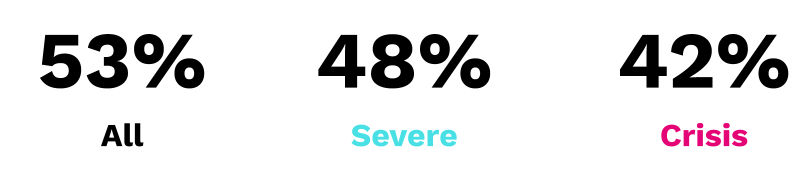

Diving deeper into the data confirmed this fact: those who are experiencing more severe crises were less likely to use our helpfulness proxies, although the rate only fell by about 10%.

Diving deeper into the data confirmed this fact: those who are experiencing more severe crises were less likely to use our helpfulness proxies, although the rate only fell by about 10%.

Comments

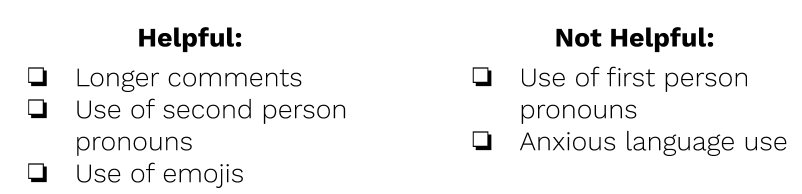

When we looked at the features of comments and helpfulness, we found that longer comments were positively correlated with our helpfulness proxies. Second person pronouns were also more likely to result in a helpfulness outcome than first person pronouns.

When we looked at the features of comments and helpfulness, we found that longer comments were positively correlated with our helpfulness proxies. Second person pronouns were also more likely to result in a helpfulness outcome than first person pronouns.

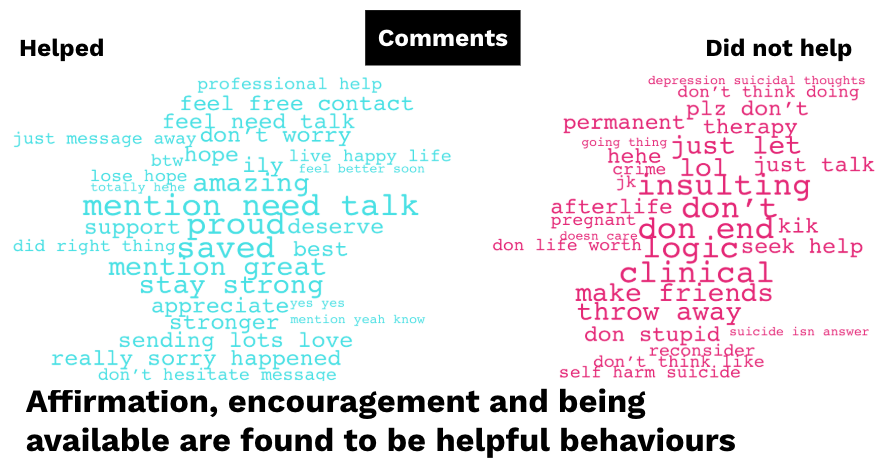

Furthermore, our analysis of the actual words and language used by commenters on the platform suggests that positive affirming language (“proud”, “did right thing”), encouragement (“stay strong”, “amazing”), and expressions of availability (“feel free contact”, “just message”, “don’t hesitate message”) were more likely to receive an indicator of helpfulness. In contrast, the use of negating language and particularly “don’t”s (“don’t be stupid”, “don’t end”, “don’t do it”) was found to be less likely to result in an indicator of helpfulness.

Furthermore, our analysis of the actual words and language used by commenters on the platform suggests that positive affirming language (“proud”, “did right thing”), encouragement (“stay strong”, “amazing”), and expressions of availability (“feel free contact”, “just message”, “don’t hesitate message”) were more likely to receive an indicator of helpfulness. In contrast, the use of negating language and particularly “don’t”s (“don’t be stupid”, “don’t end”, “don’t do it”) was found to be less likely to result in an indicator of helpfulness.

When we specifically examined comments on more serious/critical posts related to suicide and self-harm, we found that a lot of the negating language came from users dissuading their peers from engaging in self-harm: “don’t end your life”, “reconsider”, “that’s a permanent solution to a temporary problem”, etc. While this language may be coming from an intention to help, attempting to change someone’s mind in a one-off interaction without really understanding their experience may not be effective [2] [3]. We also found problematic instances of language such as “attention seeker” and “don’t be stupid” used on the platform.

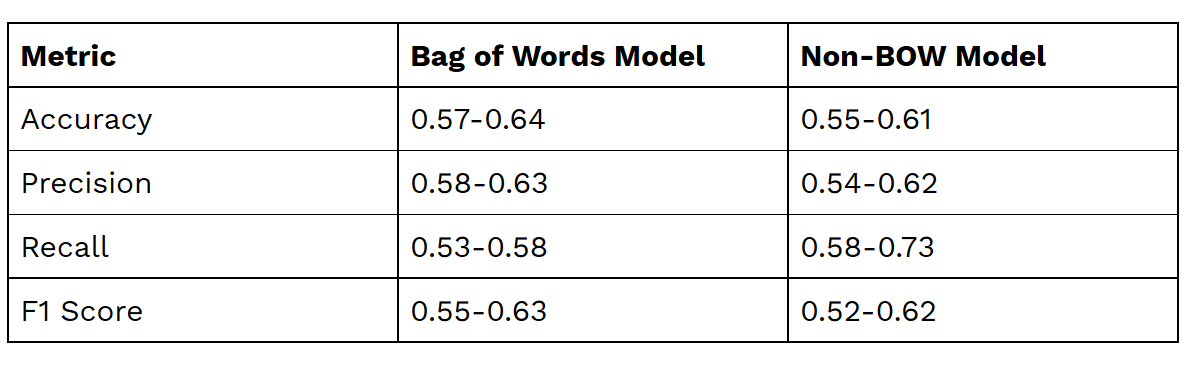

Model Performance:

References:

[1] Can, D., Atkins, D. C., & Narayanan, S. S. (2015). A dialog act tagging approach to behavioral coding: a case study of addiction counseling conversations. INTERSPEECH 2015, 339-343. https://sail.usc.edu/publications/files/Dogan-IS150788.pdf

[2] Bryan, C. J., Mintz, J., Clemans, T. A., Leeson, B., Burch, T. S., Williams, S. R., Maney, E., & Rudd, M. D. (2017, April). Effect of crisis response planning vs. contracts for safety on suicide risk in US Army Soldiers: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of affective disorders, 212, 64-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.028

[3] Rudd, M. D., Mandrusiak, M., & Joiner Jr, T. E. (2006). The Case Against No-Suicide Contracts: The Commitment to Treatment Statement as a Practice Alternative. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(2), 243-251. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/jclp.20227