Background

Research Question

Our research question this summer was as follows: What types of responses are the most beneficial to individuals sharing their mental health struggles on online peer support platforms?

In order to answer this question, we were given access to a database of over 200 million rows of public conversations, user behavior, and demographics through a data license agreement with an online peer support platform. Our goal was to use natural language processing techniques to more fully understand the types of interactions taking place on this platform and pinpoint those that seemed to be more helpful to the user seeking support.

Before we begin our discussion of our methods for doing so, however, there are a few terms that should be clarified and contextualized within the existing research.

Peer Support

Peer support, which occurs when individuals provide emotional support, knowledge, and/or practical help to each other based on a shared experience of emotional or psychological pain [1], has been studied formally as a tool for mental health support since 1991 [2].

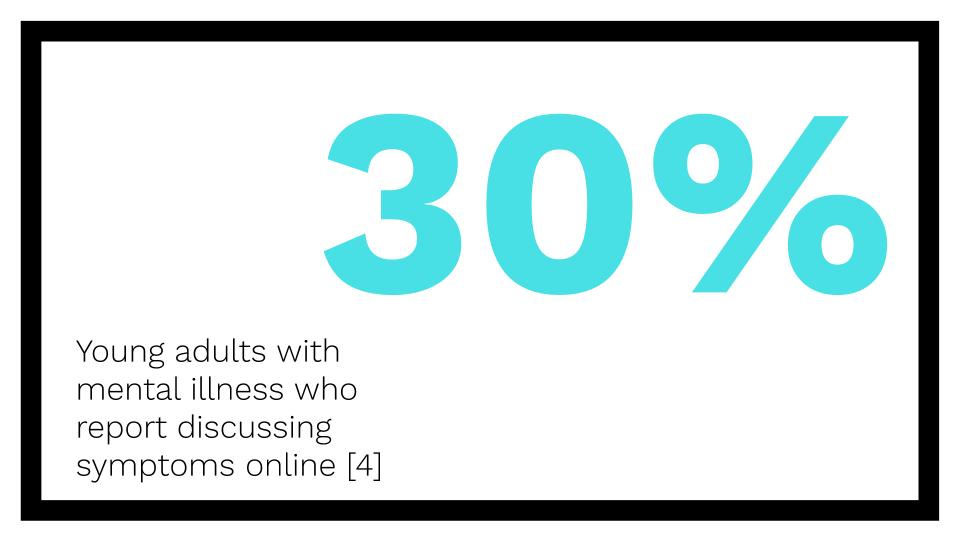

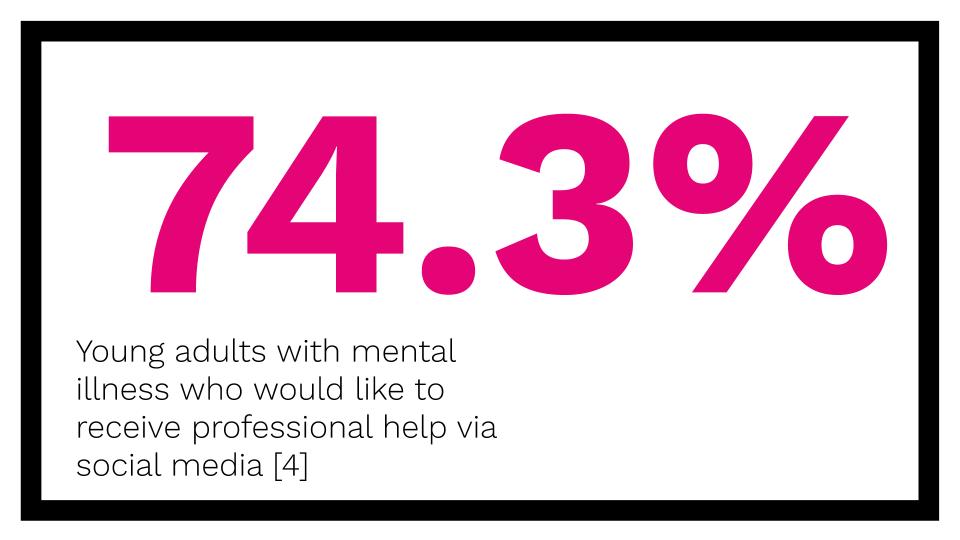

While traditional peer support has been offered through in-person interaction in small, close-knit communities, technology has enabled for the formation of online social networks of support on a much larger scale. These online peer support networks can take the form of chat rooms, social network support groups, structured messaging apps, and other such formats.

Much of the existing research into the effectiveness of online peer support has focused on adults; a 2015 systematic review looking into mental health peer-support platform usage by specifically just the young adult age demographic found only six studies that met the researcher’s criteria. Of the six studies examined, two—a randomized control trial (RCT) for anxiety and an RCT for tobacco use—found positive effects from online peer support. The four remaining studies—an RCT for eating disorders, a pre-post study of adolescent smokers, a pre-post study for depression, and a randomized trial with no control group for depression—found no effect [3].

More generally, the role of social media on young adult mental health is similarly inconclusive. A 2014 systematic narrative review of forty-three research papers found benefits of social media use to include increased self-esteem, perceived support, and opportunity for disclosure. However, it also found harmful effects including increased depression, exposure to self-harm, and cyber-bullying. The majority of the research papers studied concluded with either mixed effects or no effects on mental health at all [5].

Thus, two very different ideas about social media and online peer support can be put forth, depending on which research is cited: 1) that social media and online peer support are beneficial by giving young adults a safe and supportive environment to discuss concerns they may not otherwise broach, or 2) that social media and online peer support at best have no influence on mental health and at worst potentially aggravate depressive symptoms. Furthermore, as the authors of the peer support systematic review additionally point out, there is little research specifically on the impact of peer support on individuals with more severe mental problems, such as suicidal ideation. At the conclusion of their paper, they, like many other researchers in the field (including us), end with an urgent call for more thorough high-quality research into these platforms [3].

Motivational Interviewing

One of the most common strategies promoted for effective peer support is a method called motivational interviewing [6]. Motivational interviewing incorporates four broad styles of engaging with an individual: 1) by asking open questions, 2) by providing affirmations, 3) by engaging in reflective listening, and 4) by summarizing main themes of the discussion [7]. Typically these tools are used in contexts in which an individual is struggling with an addiction, mental health problem, or other personal challenge.

Past studies show that motivational interviewing is effective at improving health outcomes and reducing addictive behaviors [8] and can be beneficial even when used by trained professionals in a digitally-mediated environment [9]. However, there is relatively little literature with respect to motivational interviewing being used by peers in the specific context of online, asynchronous peer support communication.

Given the mental health profession’s acceptance of motivational interviewing as an effective communication style for encouraging behavioral change, we decided to incorporate the presence of motivational interviewing techniques as part of the factors we would examine while attempting to define and predict helpfulness on a peer support platform.

References:

[1] Mead, S., Hilton, D., & Curtis, L. (2001, February). Peer Support: A Theoretical Perspective. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 25(2), 134-141. Doi: 10.1037/h0095032.

[2] Davidson, L., Bellamy, C., Guy, K., & Miller, R. (2012, June). Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: a review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry, 11(2), 123-128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.009

[3] Ali K, Farrer L, Gulliver A, Griffiths KM. (2015, May 19). Online Peer-to-Peer Support for Young People With Mental Health Problems: A Systematic Review. JMIR Mental Health, 2015 2(2). Doi: 10.2196/mental.4418

[4] Birnbaum, M. L., Rizvi, A. F., Correll, C. U., Kane, J. M. & Confino, J. (2017, August). Role of social media and the Internet in pathways to care for adolescents and young adults with psychotic disorders and non-psychotic mood disorders. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 11(4), 290-295. Doi: 10.1111/eip.12237

[5] Best, P., Manktelow, R., & Taylor, B. (2014, June). Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Children and Youth Services Review, 41, 27-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.001.

[6] Allicock, M., Carr, C., Johnson, L. S., Smith, R., Lawrence, M., Kaye, L., Gellin, M., & Manning, M. (2014). Implementing a one-on-one peer support program for cancer survivors using a motivational interviewing approach: results and lessons learned. Journal of Cancer Education, 29(1), 91-98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-013-0552-3

[7] Rollnick, S., & Miller, W. R. (1995). What is motivational interviewing? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23(4), 325-334. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S135246580001643X

[8] Rubak, S., Sandbæk, A., Lauritzen, T., & Christensen, B. (2005). Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of General Practice, 55(513), 305-312. https://bjgp.org/content/55/513/305.short

[9] Farrell-Carnahan, L., Hettema, J., Jackson, J., Kamalanathan, S., Ritterband, L. M., & Ingersoll, K. S. (2013). Feasibility and promise of a remote-delivered preconception motivational interviewing intervention to reduce risk for alcohol-exposed pregnancy. Telemedicine and e-Health, 19(8), 597-604. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/tmj.2012.0247